The theology of murder

The ideological or religious roots of IS and like-minded groups go deep into history, almost to the beginning of Islam itself in the 7th Century AD.

Like Christianity six centuries before it, and Judaism some eight centuries before that, Islam was born into the harsh, tribal world of the Middle East.

"The original texts, the Old Testament and the Koran, reflected primitive tribal Jewish and Arab societies, and the codes they set forth were severe," writes the historian and author William Polk.

"They aimed, in the Old Testament, at preserving and enhancing tribal cohesion and power and, in the Koran, at destroying the vestiges of pagan belief and practice. Neither early Judaism nor Islam allowed deviation. Both were authoritarian theocracies."

As history moved on, Islam spread over a vast region, encountering and adjusting to numerous other societies, faiths and cultures. Inevitably in practice it mutated in different ways, often becoming more pragmatic and indulgent, often given second place to the demands of power and politics and temporal rulers.

For hardline Muslim traditionalists this amounted to deviationism, and from early on, there was a clash of ideas in which those arguing for a strict return to the "purity" of the early days of Islam often paid a price.

The eminent scholar Ahmad ibn Hanbal (780-855), who founded one of the main schools of Sunni Islamic jurisprudence, was jailed and once flogged unconscious in a dispute with the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad. Nearly five centuries later, another supreme theologian of the same strict orthodox school, Ibn Taymiyya, died in prison in Damascus.

These two men are seen as the spiritual forefathers of later thinkers and movements which became known as "salafist", advocating a return to the ways of the first Muslim ancestors, the salaf al-salih (righteous ancestors).

They inspired a later figure whose thinking and writings were to have a huge and continuing impact on the region and on the salafist movement, one form of which, Wahhabism, took his name.

Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab was born in 1703 in a small village in the Nejd region in the middle of the Arabian peninsula.

A devout Islamic scholar, he espoused and developed the most puritanical and strict version of what he saw as the original faith, and sought to spread it by entering pacts with the holders of political and military power.

In an early foray in that direction, his first action was to destroy the tomb of Zayd ibn al-Khattab, one of the Companions of the Prophet Muhammad, on the grounds that by the austere doctrine of salafist theology, the veneration of tombs constitutes shirk, the revering of something or someone other than Allah.

But it was in 1744 that Abd al-Wahhab made his crucial alliance with the local ruler, Muhammad ibn Saud. It was a pact whereby Wahhabism provided the spiritual or ideological dimension for Saudi political and military expansion, to the benefit of both.

Passing through several mutations, that dual alliance took over most of the peninsula and has endured to this day, with the House of Saud ruling in sometimes uneasy concert with an ultra-conservative Wahhabi religious establishment.

The entrenchment of Wahhabi salafism in Saudi Arabia - and the billions of petrodollars to which it gained access - provided one of the wellsprings for jihadist militancy in the region in modern times. Jihad means struggle on the path of Allah, which can mean many kinds of personal struggle, but more often is taken to mean waging holy war.

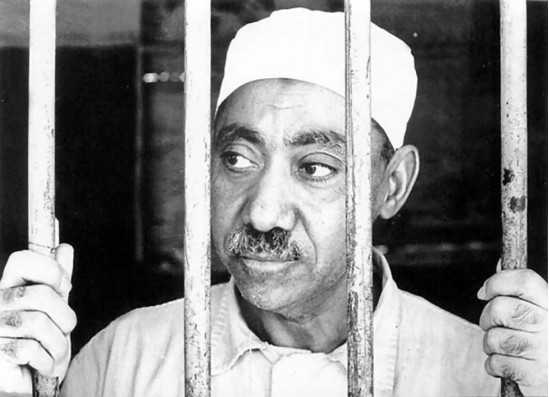

But the man most widely credited, or blamed, for bringing salafism into the 20th Century was the Egyptian thinker Sayyid Qutb. He provided a direct bridge from the thought and heritage of Abd al-Wahhab and his predecessors to a new generation of jihadist militants, leading up to al-Qaeda and all that was to follow.

Born in a small village in Upper Egypt in 1906, Sayyid Qutb found himself at odds with the way Islam was being taught and managed around him. Far from converting him to the ways of the West, a two-year study period in the US in the late 1940s left him disgusted at what he judged unbridled godless materialism and debauchery, and his fundamentalist Islamic outlook was honed harder.

Back in Egypt, he developed the view that the West was imposing its control directly or indirectly over the region in the wake of the Ottoman Empire's collapse after World War One, with the collaboration of local rulers who might claim to be Muslims, but who had in fact deviated so far from the right path that they should no longer be considered such.

For Qutb, offensive jihad against both the West and its local agents was the only way for the Muslim world to redeem itself. In essence, this was a kind of takfir - branding another Muslim an apostate or kafir (infidel), making it justified and even obligatory and meritorious to kill him.

Although he was a theorist and intellectual rather than an active jihadist, Qutb was judged dangerously subversive by the Egyptian authorities. He was hanged in 1966 on charges of involvement in a Muslim Brotherhood plot to assassinate the nationalist President, Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Qutb was before his time, but his ideas lived on in the 24 books he wrote, which have been read by tens of millions, and in the personal contact he had with the circles of people like Ayman al-Zawahiri, another Egyptian who is the current al-Qaeda leader.

Another intimate of the al-Qaeda founder Osama Bin Laden said: "Qutb was the one who most affected our generation." He has also been described as "the source of all jihadist thought", and "the philosopher of the Islamic revolution".

More than 35 years after he was hanged, the official commission of inquiry into al-Qaeda's 9/11 attack on the Twin Towers in 2001 concluded: "Bin Laden shares Qutb's stark view, permitting him and his followers to rationalise even unprovoked mass murder as righteous defence of an embattled faith."

And his influence lingers on today. Summing up the roots of IS and its predecessors, the Iraqi expert on Islamist movements Hisham al-Hashemi said: "They are founded on two things: a takfiri faith based on the writings of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, and as methodology, the way of Sayyid Qutb."

The theology of militant jihadism was in place. But to flourish, it needed two things - a battlefield, and strategists to shape the battle.

Afghanistan was to provide the opportunity for both.