Islamic State: What is the attraction for young Europeans?

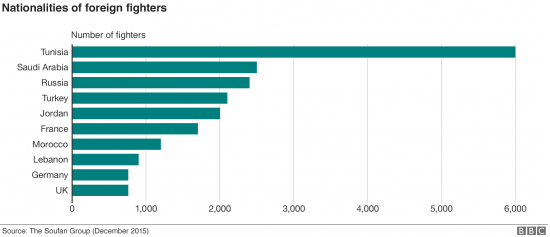

One of the biggest contingents is from Tunisia, where a detailed survey in the poorest suburbs of the capital showed clearly that the radicalisation of young people there had far less to do with extreme Islamic ideology as such than it did with unemployment, marginalisation and disillusion after a revolution into which they threw themselves, but which gave them nothing, and left them hopeless.

A rare insight into the types of people who volunteer to join IS came with the emergence in European media in March of batches of what are believed to be "secret" IS files with personal details of recruits.

The data from 2013-14 purported to identify members from at least 40 countries. It included names, addresses, phone numbers and skill sets - a potential treasure trove for intelligence agencies trying to track and prosecute nationals who have signed up with the group.

IS is also filling a desert left by the collapse of all the political ideologies that have stirred Arab idealists over the decades. Many used to travel to the Soviet Union for training and tertiary education, but communism is now seen as a busted flush. Arab socialism and Arab nationalism that caused such excitement in the 1950s and 1960s mutated into brutal, corrupt "republics" where sons were groomed to inherit power from their fathers.

In this vacuum, IS took up the cause of punishing the West and other outsiders for their actions in the region over the past century:

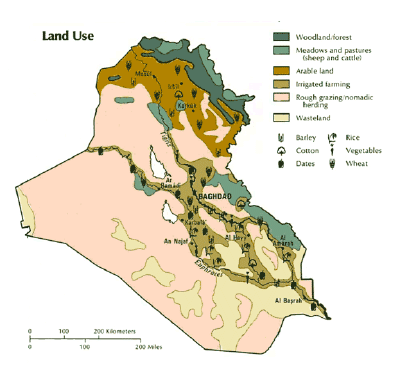

the carve-up by the colonial powers 100 years ago, drawing a border between Iraq and Syria which IS has now erased

the creation of Israel under the British mandate for Palestine, and its subsequent unswerving political and financial support by the US

Western (and indeed Russian) backing for corrupt and tyrannical Arab regimes

the Western invasion and destruction of Iraq on the flimsiest of pretexts, with the death of uncounted thousands of Iraqis

the Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo prisoner abuse scandals....

The roots of IS also lie in a crisis within Islam.

"Isil is not Islamic," said President Obama, echoing statements by many Western leaders that "IS has nothing to do with Islam".

It has.

"It is based on Islamic texts that are reinterpreted according to how they see it," says Ahmad Moussalli, professor of politics at the American University of Beirut. "I don't say they are not coming out of Islamic tradition, that would be denying facts. But their interpretation is unusual, literal sometimes, very much like the Wahhabis."

Hisham al-Hashemi, the Iraqi expert on radical groups, agrees.

"Violent extremism in IS and the salafist jihadist groups is justified, indeed blessed, in Islamic law texts relied on by IS and the extremist groups. It's a crisis of religious discourse, not of a barbaric group. Breaking up the religious discourse and setting it on the right course is more important by far than suppressing the extremist groups militarily."

Because ancient texts can be interpreted by extremists to cover their worst outrages does not implicate the entire religion, any more than Christianity is defined by the Inquisition, where burning at the stake was a stock penalty.

Extremist ideas remain in the dark, forgotten corners of history unless their time comes. And IS time came, with Afghanistan, Iraq, and everything that followed.

"Salafism is spreading in the world, in Afghanistan, Pakistan, the Arab countries," says Prof Moussalli.

He blames the Saudis for stifling the emergence of a moderate, democratic version of Islam, the "alternative Islamic discourse" to salafism that President Obama would like to see.

"A moderate Islamic narrative today is a Muslim Brotherhood narrative, which has been destroyed by the Gulf states supporting the military coup in Egypt," says Prof Moussalli, referring to the Egyptian military's ousting of the elected President Mohammed Morsi, a senior Muslim Brotherhood figure, in July 2013.

"We lost that opportunity with Egypt. Egypt could have paved the way for real change in the area. But Saudi Arabia stood against it, in a very malicious way, and destroyed the possibility of changing the Arab regimes into more democratic regimes that accept the transfer of power peacefully. They don't want it."

Saudi Arabia's ultra-conservative Wahhabi religious establishment and its constant propagation have raised ambiguity over its relations with radical groups abroad. Enemies and critics have accused it of producing the virulent strain of Wahhabism that inspires the extremists, and even of supporting IS and other ultra-salafist groups.

But Jamal Khashoggi, a leading Saudi journalist and writer who spent time in Afghanistan and knew Bin Laden, says that simply is not true

"We are at war with IS, which sees us as corrupt Wahhabis." he says.

"IS is a form of Wahhabism that has been suppressed here since the 1930s. It resurfaced with the siege of the Grand Mosque in Mecca in 1979 and spread here and there. But Saudi Arabia didn't back it at all, it saw it as a threat. So it's true that salafism can turn radical, just as the US right-wing produces some crazy lunatics."

Hundreds of people died in a two-week siege when extremist salafists took over the Grand Mosque, the holiest place in Islam, in protest at what they saw as the Kingdom's deviation from the true path.

More recently, Saudi Arabia's security forces and its Shia minority have in fact been the target of attacks by IS, and the kingdom has executed captured militants. It has an active deradicalisation programme.

But Mr Khashoggi agrees that the Saudis made a huge mistake when they backed the overthrow of the elected Muslim Brotherhood president in Egypt and the subsequent crackdown on the movement, which has pushed political Islam into the arms of the radicals.

"There were no pictures of Isis, Bin Laden or al-Qaeda in Tahrir Square," he says. "It was an opportunity for democracy in the Middle East, but we made a historical blunder for which we are all paying now."

But the Kingdom's extreme conservatism, its distaste for democracy, and its custodianship of the shrines in Mecca and Medina to which millions of Muslims make pilgrimage every year, have made it one of the main targets for calls for an unlikely reformation within Islam as part of the battle to defeat IS and other extremist groups.

"We must accept the fact that Islam has a crisis," says a senior Sunni politician in Iraq.

"IS is not a freak. Look at the roots, the people, the aims. If you don't deal with the roots, the situation will be much more dangerous. The world has to get rid of IS, but needs a new deal: reformation, in Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, al-Azhar [the ancient seat of Sunni Islamic learning and authority in Cairo]."

"You can't kill all the Muslims, you need an Islamic reformation. But Saudi and Qatari money is blotting out the voices so we can't get anywhere. It's the curse of the Arab world, too much oil, too much money."