Regional rivalry

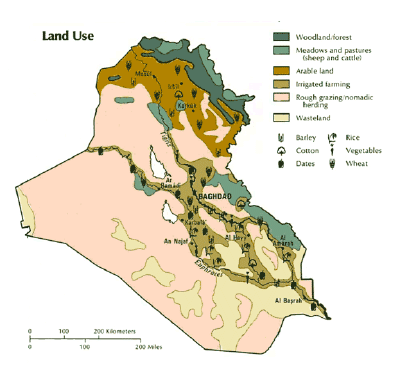

IS is at the heart of yet another of the region's burning themes - the strategic geopolitical contest, the game of nations, that is taking place as Syria and Iraq disintegrate.

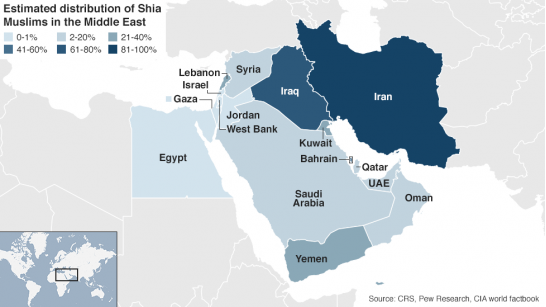

When the US-led coalition destroyed the Iraqi state in 2003, it was breaking down the wall that was containing Iran, the region's Shia superpower, seen as a threat by the Saudis and most of their Sunni Gulf partners since its Islamic revolution in 1979.

Iran had for years been backing anti-Saddam Iraqi Shia factions in exile. Through those groups, the empowerment of the majority Shia community in Iraq after 2003 gave Iran unrivalled influence over Iraqi politics.

The arrival of the IS threat led to even more Iranian penetration, arming, training and directing the Shia militia who rose in defence of Baghdad and the South.

"If it weren't for Iran, the democratic experiment in Iraq would have fallen," says Hadi al-Ameri, leader of the Iranian-backed Badr Organisation, one of the biggest Shia fighting groups.

"Obama was sleeping, and he didn't wake up until IS was at the gates of Erbil. When they were at the gates of Baghdad, he did nothing. Were it not for Iran's support, IS would have taken over the whole Gulf, not just Iraq."

For Saudi Arabia and its allies, Iranian penetration in Iraq threatens to establish, indeed largely has, a Shia crescent, linking Iran, Iraq, Syria under its minority Alawite leadership, and Lebanon dominated by the Iranian-created Shia faction Hezbollah.

From the outset of the war in Syria, the Saudis and their Gulf partners, and Turkey, backed the Sunni rebels in the hope that the overthrow of Assad would establish Sunni majority rule.

So then a north-south Sunni axis running from Turkey through Syria to Jordan and Saudi Arabia would drive a stake through the heart of the Shia crescent and foil the Iranian project, as they saw it.

That is essentially what IS did in 2014 when it moved back into Iraq, took Mosul and virtually all the country's Sunni areas, and established a Sunni entity which straddled the suddenly irrelevant border with Syria, blocking off Shia parts of Iraq from Syria.

If IS had just stayed put at that point and dug in, who would have shifted them? Had they not gone on to attack the Kurds, the Americans would not have intervened. Had they not shot down a Russian airliner and attacked Paris, the Russians and French would not have stepped up their involvement.

"Had they not become international terrorists and stayed local terrorists, they could have served the original agenda of dividing the Arab east so there would be no Shia crescent," says Prof Moussalli.

We may never know why they did it. Perhaps their virulent strain of salafism just had to keep going: Remaining and Expanding.

Could they now just row back and settle in their "state", stop antagonising people, and eventually gain acceptance, just as Iran has after its own turbulent revolution and international isolation?

It seems unlikely, for the same driving reasons that they made that escalation in the first place. And even if IS wanted to, the Americans also seem set on their course, and they have proven implacable in their pursuit of revenge for terrorist outrages.

But what is the alternative? Given the problem of assembling capable ground forces, can the Americans be complicit in a takeover of Mosul by Iranian-backed Shia militias, and of Raqqa by Russian- and Iranian-backed Syrian regime forces or other non-Sunni groups like the Kurds? Is their hostility to IS so strong that they would watch the Iranians connect up their Shia crescent? And would the Saudis and Turks go along with that?

There are no easy answers to any of the challenges posed by IS in all the strands of crisis that it brings together.

That's why it's still there.

Credits:

Author: Jim Muir

Editor: Raffi Berg

Production: Ben Milne, Susannah Stevens

Graphics: Henry Clarke Price

- << Prev

- Next