Iraq fiasco

The fallout from the 9/11 attacks changed things radically for the jihadists in late 2001. The US and allies bombed and invaded Afghanistan, ousting the Taliban, and launching a wider "War on Terror" against al-Qaeda.

Bin Laden went underground, and Zarqawi and others fled. The dispersing militants, fired up, badly needed another battlefield on which to provoke and confront their Western enemies.

Luck was on their side. The Americans and their allies were not long in providing it.

Their invasion of Iraq in the spring of 2003 was, it turned out, entirely unjustified on its own chosen grounds - Saddam Hussein's alleged production of weapons of mass destruction, and his supposed support for international terrorists, neither of which was true.

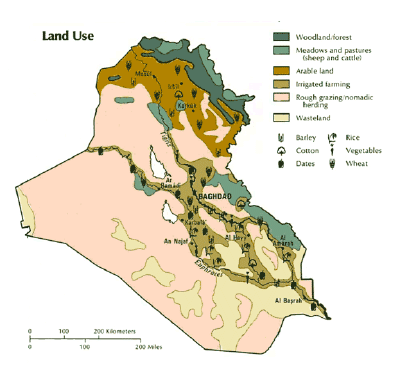

By breaking up every state and security structure and sending thousands of disgruntled Sunni soldiers and officials home, they created precisely the state of "savagery", or violent chaos, that Abu Bakr Naji envisaged for the jihadists to thrive in.

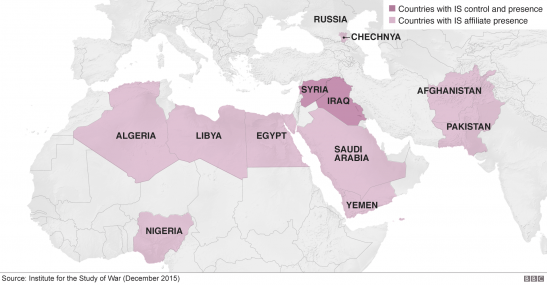

Iraq was on the way to becoming what US officials are now calling the "parent tumour" of the IS presence in the region.

Under Saddam's tightly-controlled Baath Party regime, the Sunnis enjoyed pride of place over the majority Shia, who have strong ties with their co-religionists across the border in Iran.

The US-led intervention disempowered the Sunnis, creating massive resentment and providing fertile ground for the outside salafist jihadists to take root in.

They were not long in spotting their constituency. Abu Musab Zarqawi moved in, and within a matter of months was organising deadly, brutal and provocative attacks aimed both at Western targets and at the majority Shia community.

Doctrinal differences between the two sects go back to disputes over the succession to the Prophet Muhammad in the early decades of Islam, but conflict between them is generally based on community, history and sectarian politics rather than religion as such.

Setting himself up with a new group called Tawhid wa al-Jihad (Tawhid means declaring the uniqueness of Allah), Zarqawi immediately forged a pragmatic operational alliance with underground cells of the remnants of Saddam's regime, providing the two main intertwined strands of the Sunni-based insurgency: militant Jihadism, and Iraqi Sunni nationalism.

His group claimed responsibility for several deadly attacks in August 2003 that set the pattern for much of what was to come: a suicide truck bomb explosion at the UN headquarters in Baghdad that killed the envoy Sergio Vieira de Mello and 20 of his staff, and a suicide car bomb blast in Najaf which killed the influential Shia ayatollah Muhammad Baqir al-Hakim and 80 of his followers. The bombers were salafist jihadists, but logistics were reportedly provided by underground Baathists.

The following year, Zarqawi himself was believed by the CIA to be the masked killer shown in a video beheading an American hostage, Nicholas Berg, in revenge for the Abu Ghraib prison abuses of Iraqi detainees by members of the US military.

As the battle with the Americans and the new Shia-dominated Iraqi government intensified, Zarqawi finally took the oath of loyalty to Bin Laden, and his group became the official al-Qaeda branch in Iraq.

But they were never really on the same page. Zarqawi's provocative attacks on Shia mosques and markets, triggering sectarian carnage, and his penchant for publicising graphic brutality, were all in line with the radical teachings he had imbibed. But they drew rebukes from the al-Qaeda leadership, concerned at the impact on Muslim opinion.

Zarqawi paid little heed. His strain of harsh radicalism passed to his successors after he was killed by a US air strike in June 2006 on his hideout north of Baghdad. He was easily identified by the tattoos he had never managed to get rid of.

The direct predecessor of IS emerged just a few months later, with the announcement of the Islamic State in Iraq (ISI) as an umbrella bringing the al-Qaeda branch together with other insurgent factions.

But tough times lay ahead. In January 2007, the Americans began "surging" their own troops in Iraq from 132,000 to a peak of 168,000, adopting a much more hands-on approach in mentoring the rebuilt Iraqi army. At the same time, they enticed Sunni tribes in western al-Anbar province to stop supporting the jihadists and join the US-led Coalition-Iraqi government drive to quell the insurgency, which many did, on promises that they would be given jobs and control over their own security.

By the time both the new ISI and al-Qaeda leaders were killed in a US-Iraqi army raid on their hideout in April 2010, the insurgency was at its lowest ebb, pushed back into remote corners of Sunni Iraq.

They were both replaced by one man, about whom very little was publicly known at the time, and not much more since: Ibrahim Awad al-Badri, better known by his nom de guerre, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

Six eventful years later, he would be proclaimed Caliph Ibrahim, Commander of the Faithful and leader of the newly declared "Islamic State".